Art and pseudoscience

Who will ever do anything better than that propeller?

Last time I wrote I went on about my general interest in aesthetics of scientific imaging and systems of logic. I want to carry that on by looking at drawings practices as if they were engaged in this type of knowledge production. I’m casting a pretty wide net, so think of it more as free association rather than a schema. I’ll roughly be moving on a gradient that moves from the drawing as data to the drawing as schematic, from physical phenomena to a cool system of logic.

Line as seismograph

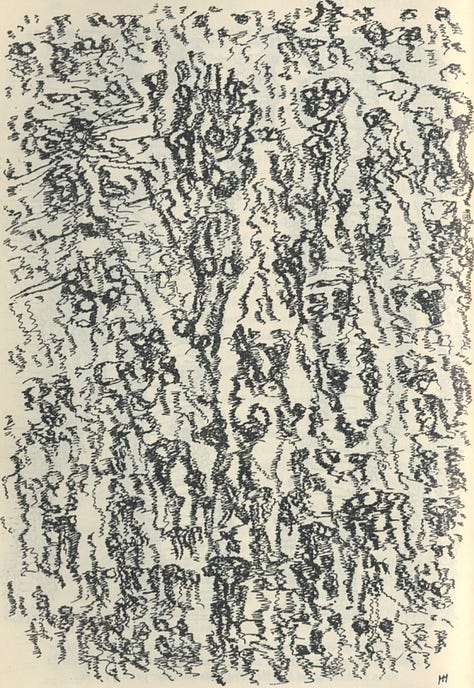

Henri Michaux is hardly a painter, hardly even a writer, but a conscience—the most sensitive substance yet discovered for registering the fluctuating anguish of day-to-day, minute-to-minute living.

—John Ashbery

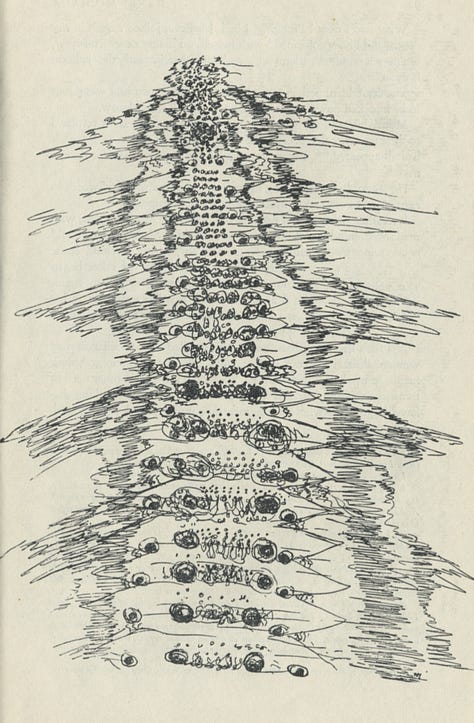

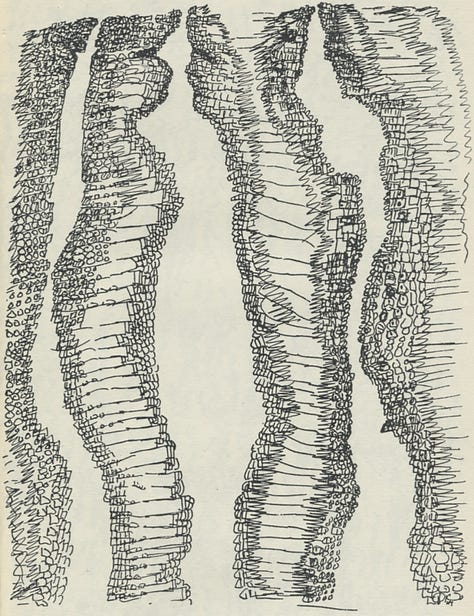

Henri Michaux’s mescaline drawings seem to best express how the line records mental activity. I experience his strokes as readouts of anxiety, restlessness, agitation—graphing the body in its dimension as a natural phenomenon. This is not coincidental, Michaux describes his awareness of consciousness (the vibratile carpet), or what happens below it, using a range of scientific imagery.

This vibratile carpet, which had something in common with electrical discharges with ramified sparks, as well as with magnetic spectra, a certain something that trembled, that burned, that tingled, like spasms turned into nerves, this tree with fine branches, that could also be lateral bursts, that tempestuous fluid, contractile, shaken, effervescent, but elastically held and kept from overflowing through some sort of surface tension, that nervous projection screen, even more enigmatic than the visions that arose on it

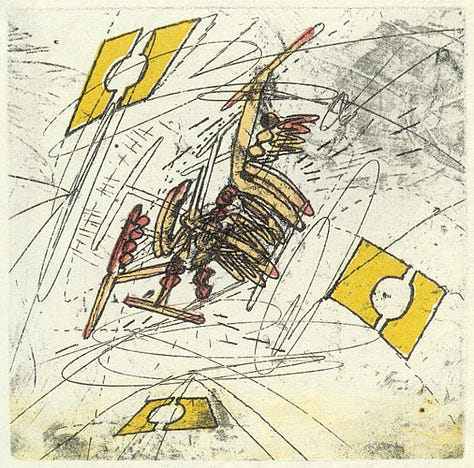

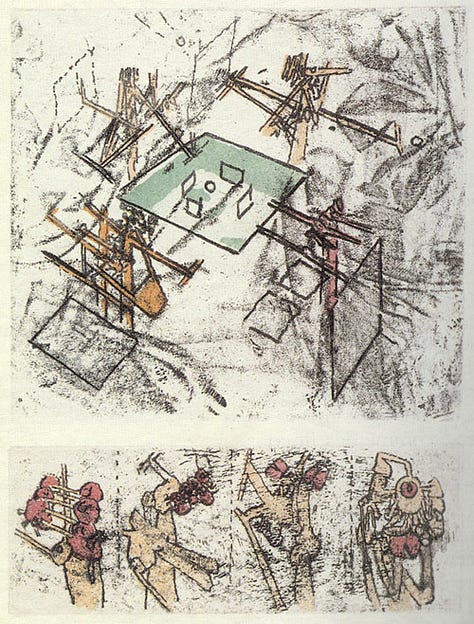

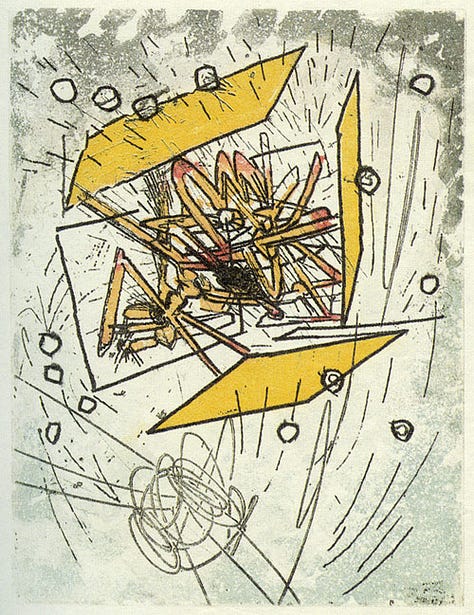

Picture plane as particle collider

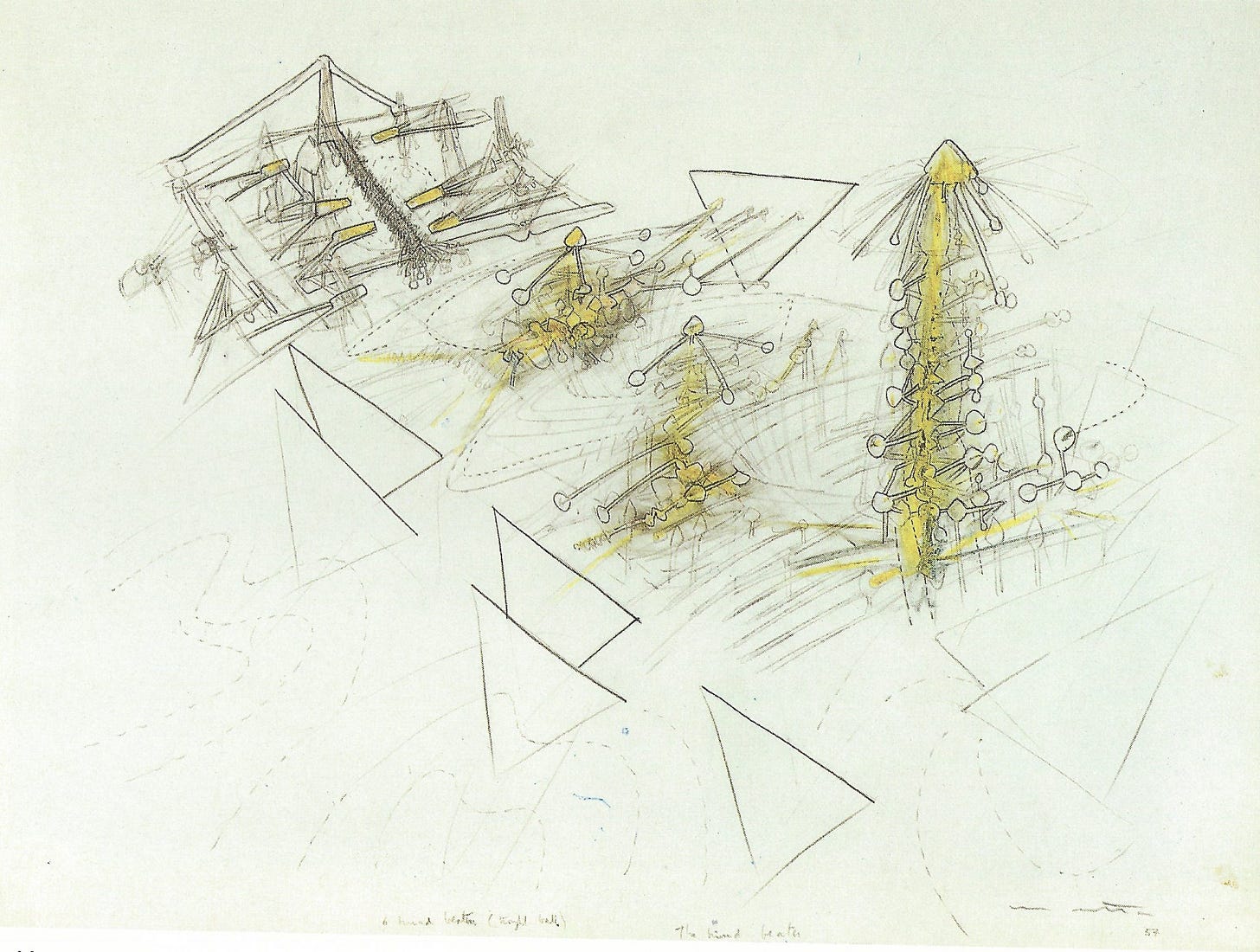

Roberto Matta’s etchings takes a view one step removed from the ‘recordings’ above. They appear as schematics that describe the organism in its capacity as a particle, under study, bombarded, energetic. Here the action doesn’t take place on the surface of the page, but within it, allowing us to appreciate the picture plane as a space of action where impulses are unleashed in order to be studied. Where for Michaux the page gives these forces form, Matta shows us the mechanisms built to corral them.

Figure/Ground as field

In contrast the to the “line” which suggests a classical physics model of cause and effect, the (force) field) is a space where figure and ground appear knit out of a tense mesh of marks. Mondrian’s early tree paintings seem a good example of this, with colour field painting as this principle taken to its abstract limits. Van Gogh, Edvard Munch, are other approachable examples of work where the ground is activated, brought to the fore. This is such a general point, but I feel it is a fun way to reimagine the impressionist and expressionist as a type of pansychism, where all things are endowed with the same energy.

Medium as matter

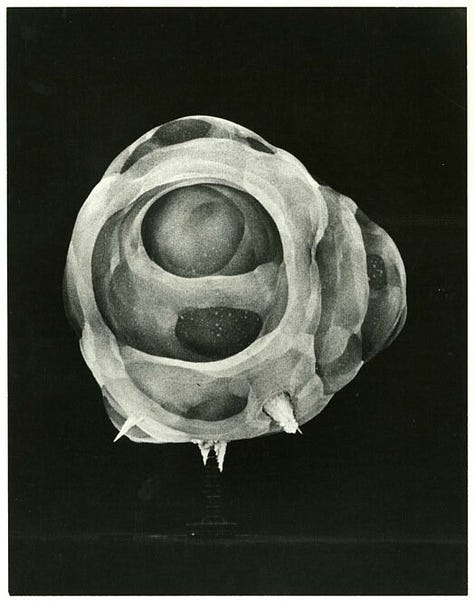

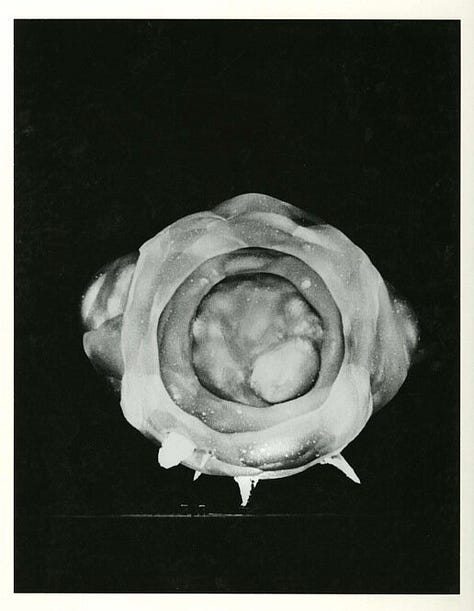

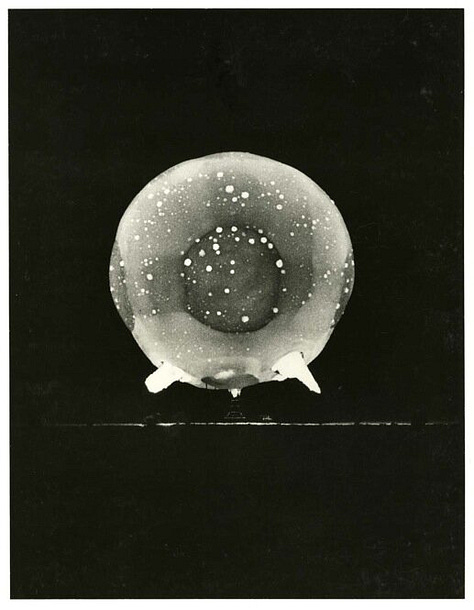

In Ab Ex artists I see a desire to explore the matter of their medium, and the volatility latent within it. Their utilisation of unprimed canvas, irreverence to unpainted portions of the picture, and self reflexive focus on the brushstroke impart a feeling of being at the ground floor of reality. Looking at Pollock, Motherwell, or Joan Mitchell, I get the impression of a new world coming into being, each stroke an atom of its own. I’m reminded of the forces unleased in the early pictures of the trinity test.

Painting the invisible world

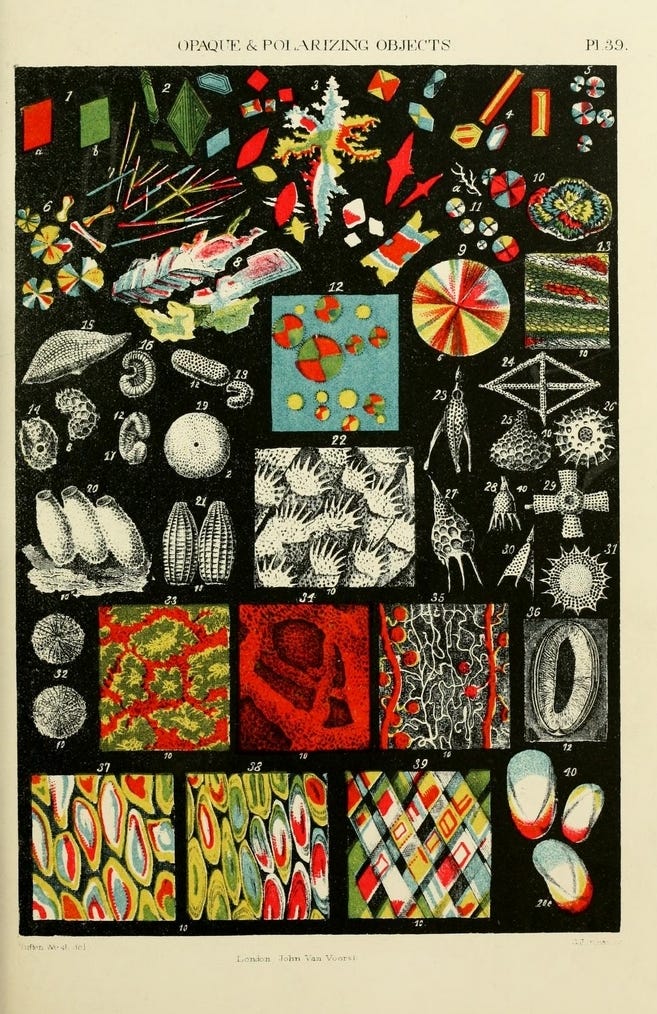

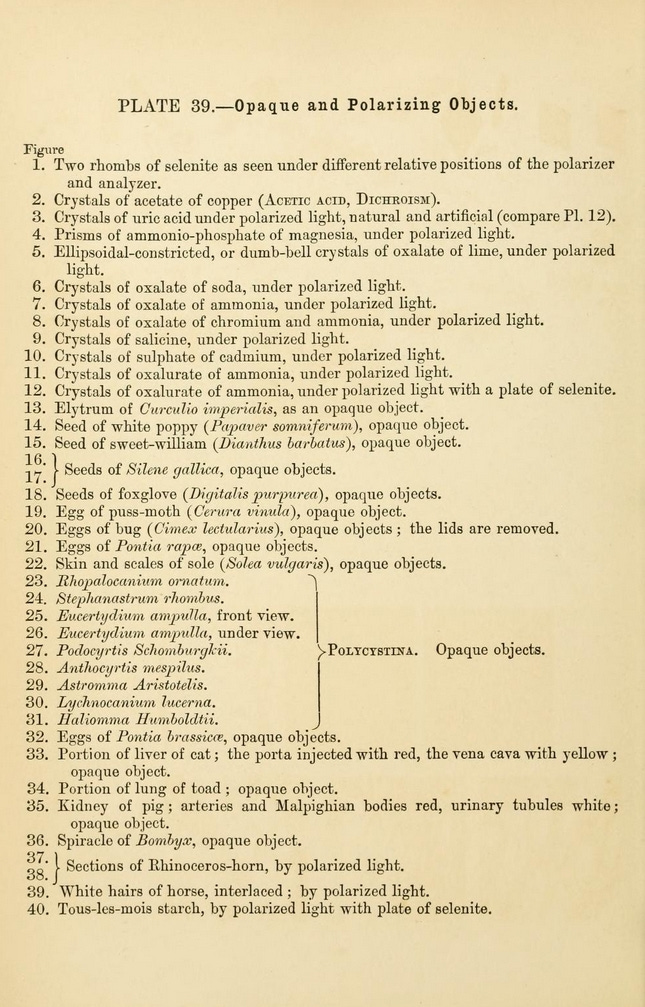

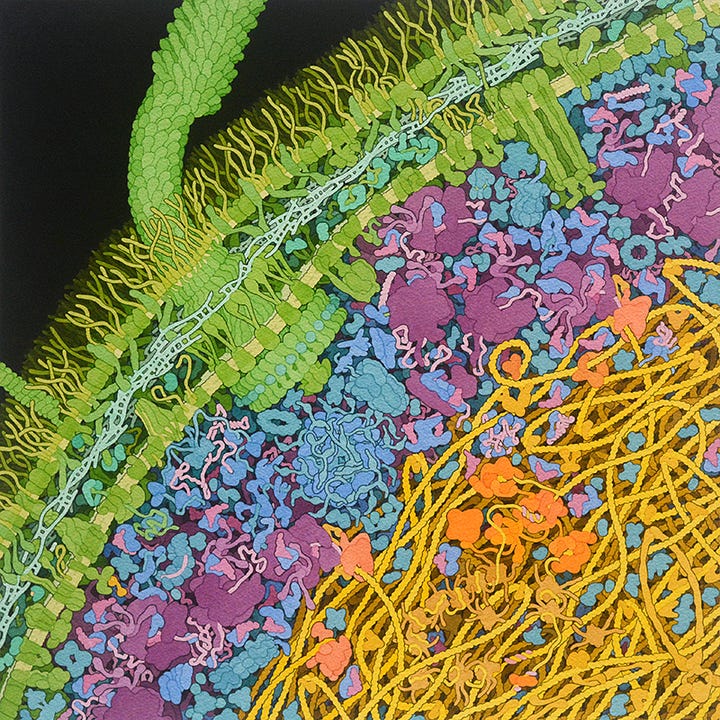

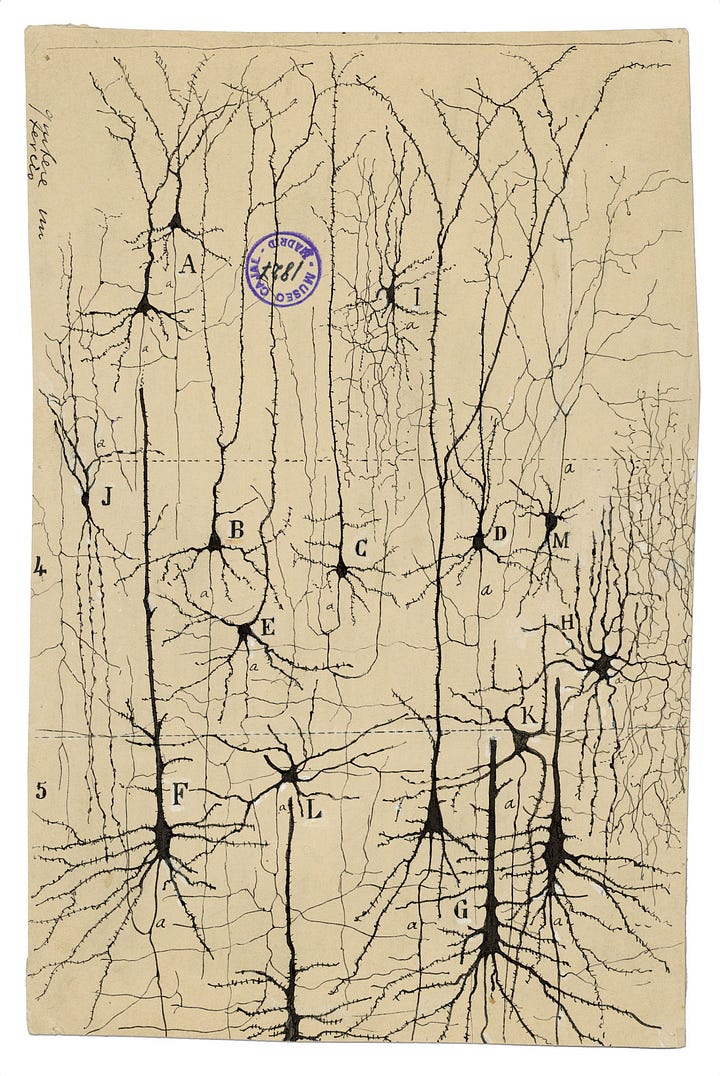

Moving away from abstraction, there is the obvious point that prior to photography scientific illustration filled in the gaps. Drawings of microorganisms, DNA, crystal structures, etc all purport to show us the structure of the world made visible while doubling as mesmerizing artifacts. I think there is an interesting contradiction in this mode, which is the simultaneous desire to be photoreal and but make ideal depictions. For example we have Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s drawings of brain cells as against the visualization of the DNA double helix. In the first case there’s not much more for me to say here other than to acknowledge the beauty of these renderings. For the second I am interested in this need to “average” the thing perceived, and how this forms an aesthetic of objectivity. Audubon is an example of this on the human scale. But the farther we move down in scale the more messy these representations become, eventually reduced to the level of schematic. Think Feynman diagrams. This gradient from the particular to the universal is fascinating, intractable.

Diagrammatic Art

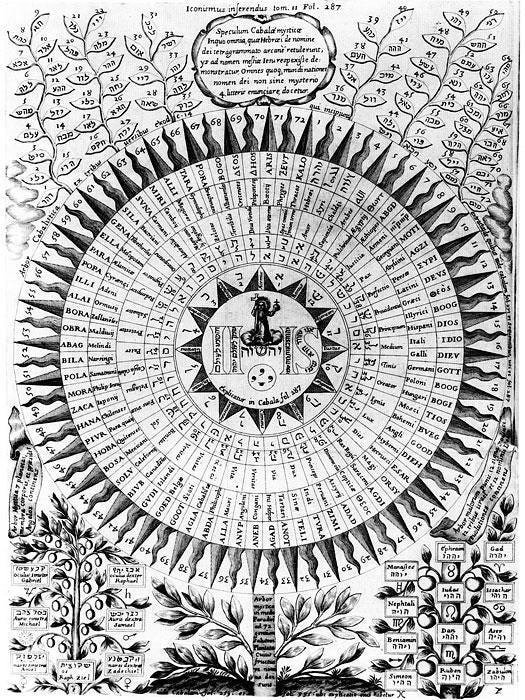

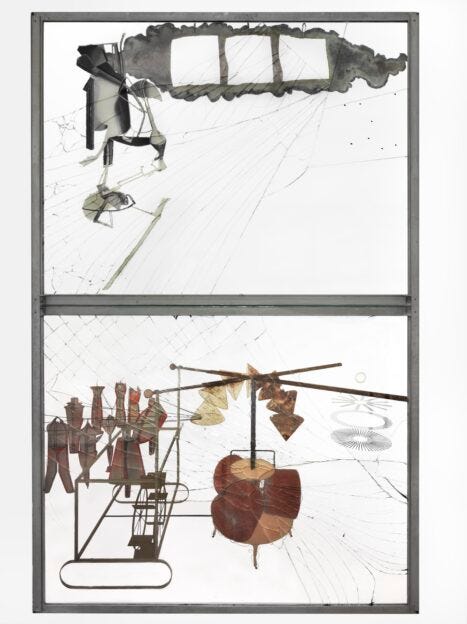

Now we get to the best part, where science and drawing have to kiss. Diagrams, graphing cause and effect, classifying, spatially ordering, visually rationalizing. The aesthetic of diagrams could be its own post, but I don’t have the knowledge to attempt anything more comprehensive. Suffice to say that as the artistic companions to science with a rich visual history they are the obvious mode with which to pantomine. Consider Duchamp alongside Christian mysticism, a reminder of how spirit has been exsanguinated into physical forces, machines, mechanisms.

The placement of the Bachelors' nine "shots" (which never do reach the waiting Bride) was effected by dipping matches in wet paint and firing them from a toy cannon at the Glass. The forces of gravity, wind, and "personalized chance" were thus substituted for the workings of his own conscious hand, always in the spirit of hilarity that Duchamp once paraphrased as that "necessary and sufficient twinkling of the eye," and always with the same meticulous, painstaking attention to detail that a scientist might apply to a controlled nuclear experiment

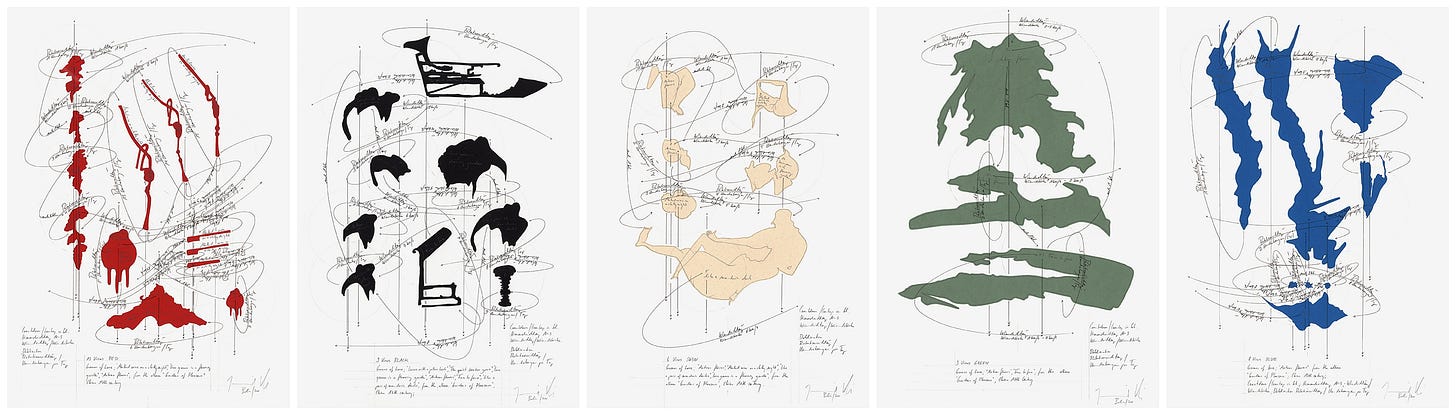

Jorinde Voigt is an artist I admire for taking this to its limit, maximally diagramming music, eroticism, mundane activity, testing the presumption that any document can be commensurate with lived experience. Alongside her lines and annotation there are ineffable fields of colour, gold foil, shadows of the thing purportedly represented. Bodies in motion pinned to the page like taxidermied insects.

I’m at the limit here, but there are tons of examples to draw from. Process art shifted focus to rules, procedures, machines for composition (think Sol Lewitt, surrealist games, Fluxus). In literature movement such as algorithmic writing, Oulipo, Fluxus. In performances fields we have musical scores, aleatoric music, (John Cage, Stockhausen), and process based composers like Steve Reich. This new work appears to parallel the rise of computing, dealing with emergence, networks, systematicity, algorithm. Much of this has been made mundane by the internet based information age. Now the black box of AI is in need of visualization, aestheticizing our new alienation to knowledge production. More than ever we remain tangled in models, captured by them, against the limits of what can, or should, be simulated.

Already the knowing animals are aware that we are not really at home in our interpreted world. — Rilke